|

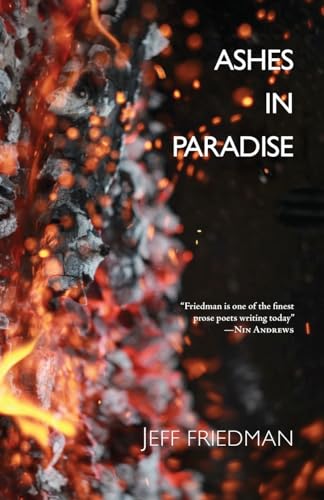

The Mackinaw Talks to Jeff Friedman About His New Book, Ashes in Paradise

The Mackinaw: Tell us something about your writing journey, from poetry to flash fiction to prose poetry. How important are these distinctions and genre labels to you as a writer? Jeff Friedman: I was always a storyteller. For the most part, my verse poems were lyricized narratives, informed/influenced by biblical stories and rhythms and by Philip Levine, James Wright, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and the Spanish and surrealist poets that I grew up with. Eventually, the poems turned into blocks of prose—the lines gone. I was writing prose pieces that might be called fables, mini tales, micro stories, parables, comic sketches, vignettes or prose poems. I think the change occurred the year my mother and five other people close to me died, and then I ended up in the hospital for an emergency procedure. Seemed like every time I picked up the phone, there was more bad news. Everything that happened must have played a big part in my shifting to prose poetry. What I needed to say, the other parts of me that needed to be expressed, necessitated some kind of letting go. I remember trying to write verse poems one day and the next, prose pieces. Finally I had to let the verse poems go to move on. My book Pretenders contained both prose poems and verse. But my next book, Floating Tales was all prose poetry and micros. Same with my new book, Ashes in Paradise, both books centered in surrealism and fabulism. Pretenders also. How important are these distinctions and genre labels to you as a writer? It’s more important to me to write a strong piece than to worry about what it is. I used to think if the piece started with dialogue, it was probably going to be a story, and if it started with an image or a repeating sound it would be a poem. But that didn’t hold up. And many of my pieces have had a dual life in journals and anthologies as prose poems and as micro stories, for example, “Not Everything Was in My Father’s Will,” and “Lost Memory” (both from Ashes in Paradise). I’d like to think that the prose poems are driven by their music, and the micros/flashes by the way events unfold and change occurs, but often the two overlap each other. For you, what is the definition of a prose poem? The prose poem is a chameleon; just when I think I know what it is, it changes shape and then changes shape again; it’s a flicker of gold on the mirror of a river, a thousand faces rising to the surface. It’s a sentence looking for a paragraph, a paragraph inside a sentence. It’s a paradox with wings, flying into a luminous haze. Tell us about your writing process. What does a day in the life of one of your prose poems look like? I start writing early in the morning when it’s still dark. I like to have that private space in which to work. Usually, I read some prose poems before I start writing. And I also look over what I’ve written the day before, and possibly I read some other pieces of mine that are complete to see if new ideas come to mind. One strange thing about my writing process is that if I sit down to write early in the day and even just write one sentence or one image, that allows me to be able to write later in the day. If I don’t write in the morning, then I’m unlikely to be able to write in the afternoon. On a good writing day, I generate a draft pretty quickly, and sometimes those drafts are nearly complete, requiring just a little tweaking, but other times, my pieces go through many drafts. I keep working until I get it or until I don’t. If the piece doesn’t seem right after many drafts, I put it away for weeks or even months before I come back to it. It’s important for me to commit to an image, idea, thought, sound and write it out. I know I’m in trouble when I keep backing out of each thing that comes to mind. Often that happens because I feel that I’ve been down that corridor too many times before. What are some of the ideas and themes that you address in Ashes in Paradise? How are these similar or different with the things that drive you in your other collections? The book explores themes of connection and disconnection, distance from others, hope and failed expectations, familial and erotic love, history and myth, masks and disguises, truth and the distortion of reality, and mortality. For me the title of the book, implies some kind of journey back to paradise, that all the sacrifice to get there has left only ashes. I like what Denise Duhamel says about it: “Jeff Friedman shows us the flexibility, stamina, and hilarity of the prose poem in his latest book Ashes in Paradise. Fabulist renditions of the political horror and unease of our times (the pandemic, police violence, political unrest) are set against wry, revisionist Biblical tales and neo-surreal domestic dramas (discounted orgasms delivered by Amazon Prime).” There are many ways this book intersects the themes of Floating Tales, but that book was centered in Italo Calvino’s notion of “lightness.” And this book, informed by the pandemic and the brutality of the Trump administration, and then the insurrection on January 6th, is darker, heavier, edgier, full of unease. However, there are many pieces such as “Spring in Air,” “Orgasms on Amazon Prime,” “Somebody’s Got My Hair,” “Shape” that are quite entertaining. I guess the book is darkly funny maybe in contrast to the giddiness of Floating Tales and The House of Grana Padano cowritten with Meg Pokrass. Do you have a favourite poem in the collection? Tell us about how it came together. I have a number of favourites, but I’ll just choose one, “Lost Memory,” published as a prose poem and then selected for Best Microfiction 2021. When I was in second grade, I had double pneumonia and missed most of the school year. My mother, fearing that my teacher would think I was doing nothing but reading comic books and watching TV, invited the teacher and my classmates to our apartment to show her that I was actually doing something educational. She coerced me into memorizing the names of all the presidents and telling a little story about a number of them. I was pretty sick for many months. A few years ago, I was recounting this experience for my older sister who had totally forgotten it had ever happened. And several months after that, she told me that she had had double pneumonia and our mother had invited the other students over to the apartment—almost the identical story—but she was asked to play “Malaguena” on our ridiculously out-of-tune piano. An argument ensued about who had had double pneumonia. It suddenly became her memory, her experience. I wrote a number of pieces in which a scene was created with the two of us arguing over who owned the memory. I thought it was a great subject for a comic piece, but somehow, it never really came together when I tried to stay true to the moment. Then I got the idea of a blue jar as a metaphor for the memory and that opened up the imaginative world of the piece. Was there a poem you wrestled with, that was particularly challenging to write? Why? I think the pieces that were most difficult to write about were “Boy with Holes,” “Last Truth,” “Truth,” and other pieces dealing with racism, the distortion of reality, and the attack on truth that’s going on right in front of us every day. I had to find an approach to writing about these subjects that didn’t seem exploitative, pretentious or didactic. Emily Dickinson’s famous statement, “Tell the truth, but tell it slant,” was a kind of guiding light. “Spring in Air” was also difficult to write in that it was a comic piece about having to wear masks and stay six-feet apart in the grocery store—the fear involved in going to the grocery store during the pandemic. In my piece, the speaker sneezes three times in the line waiting to pay for his groceries, and that sets off a humorous chain of events. Who are some of your favourite prose poets? What is it about their work that inspires you? Is there a specific book of prose poems that you find yourself inside over and over again? First, let me say that I really like the bookshelf section of Mackinaw, where you’ve listed so many important books of prose poetry. It’s like you’re providing a map of the prose poem with all its different territories. Well, to start, and at this present moment, I’d have to name the prose poetry friends with whom I exchange work: Nin Andrews, Dzvinia Orlowsky (Bad Harvest), Kathleen McGookey, Celia Bland, Meg Pokrass (Spinning to Mars), and Ross Gay (his books of Delights, brief essays that often read like prose poems). I like how the personal intersects with history in all their work, their surrealism, their stunning images, their empathy. They are all good storytellers, and there is much humour in their work. I think of shaping sensibilities: When the change came in my work, I was greatly influenced by Zbigniew Herbert’s prose poems; James Wright’s “The Wheeling Gospel Tabernacle” and “Honey”; Kafka’s “Little Fable,” “Sirens,” and so many of his other short pieces; many pieces by Max Jacob, and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. But over the last twenty-five years I’ve learned from so many other prose poets (or poets who have written books of prose poems), including Charles Simic (The World Doesn’t End); Harryiette Mullen (Sleeping with the Dictionary); James Tate (Memoir of the Hawk); Ana Maria Shua (I consider many of her pieces to be prose poems); Suniti Namjoshi (Blue Donkey Fables); Russell Edson (The Tunnel); Denise Duhamel; Peter Johnson; Philip Levine (his sequence of prose poems in News of the World); Aesop’s Fables (translation by Jack Zipes); Robert Scotellaro; Anne Carson (Short Talks); and Eduardo Galeano (Book of Embraces and the Creation pieces in Memory of Fire). I know I’m forgetting prose poets I’d put on this list. I’ve learned from so many different prose poets and prose poems difficult to even make a list. I guess this is kind of a collage of my consciousness. When I’m looking for inspiration, I go back to Zbigniew Herbert’s prose poetry in his Selected Poems, translated by Peter Dale Scott and Czeslaw Milosz. I’ve been inside that book over and over since graduate school. I first read Herbert’s poems in one of Larry Levis’s workshops. What are some compelling or curious things about you that aren’t related to writing? What are your other interests? What else is important to you? I walk two to four hours a day. I’ve gotten to be a fairly decent cook over the years. I’ve been trying to learn guitar, and after so many years, I can honestly say, I’ve improved from awful to terrible. Not ready to go on the road. I also take Tai Chi and if somebody were to throw a slow-motion punch at me twenty-five years from now, I may be able to block it or get out of the way, though my teacher thinks that’s unlikely. What books are you reading right at this moment? I have to look on my nightstand for that. Okay, Immense World by Ed Yong, Hell, I love Everybody: The Essential James Tate (a great selection of his work just the right length), Folk Music: A Biography of Bob Dylan in Seven Songs, Antarctica by Claire Keegan, Recollections of My Non-Existence by Rebecca Solnit, Opening the Hand by W.S. Merwin, Cronicas by Clarice Lispector, The Invisible Universe by Matthew Bothwell, Genesis (which I’ve read repeatedly through the years), and Quick Adjustments by Robert Scotellaro (his wonderful new book of micros). I often jump from book to book, reading a chapter or 5-10 pages until I settle on something for the night. I do the same thing with movies on streaming services…I watch 15 minutes at a time and then move on to something else until I click into the right thing. If I like a book, I’m a little sad when I finish it. I love reading books that have short chapters or sections, perfect for my reading habits. What’s next for Jeff Friedman? I’m working on a chapbook or a book for Mark Givens’ Bamboo Dart series. Jazz composer, saxophonist and poet Roy Nathanson and I have also been writing a book of poems in which the poems respond to each other. I’ve worked with Roy on many projects before and joined his group Sotto Voce on stage many times. We’ve also written some songs together. Roy is an amazing composer and musician and a strong poet also. And then Meg Pokrass and I are writing a second collaborative book on Google Drive and Zoom. We’re writing each of these pieces together as improvisations. That’s been really fun. The pieces emerge from our love of comedy, and from having a great time together. She’s a fantastic flash fiction writer and prose poet. We’re planning some readings together this coming October. ** Click here to view Jeff Friedman's new book, Ashes in Paradise, on Amazon. |